|

| Our charmingly rustic and tranquil accommodations in Les Houches |

It’s been more than two months since the biggest race of my life, and it’s a testament to just how insanely busy life has been since then that I’m just now finding some time to sit down and write this race report, our first blog post—incredibly—since the end of August. At this point the race experience feels surreal, as it it were a dream. Did that really happen? And then I look at these photos and get lost in my memories of the event and realize yes, it very much happened.

For those who want the extremely abridged version of events: In the moment of the race, and solidified in my mind since then, I came to three primary conclusions about the CCC—1) It was the most beautiful course I’ve run, 2) It was the most difficult course I’ve run, and 3) It was the most competitive race I’ve done. (Click on any of the photos to open a full-screen slideshow.)

|

| Atop the Aguille du Midi with Mont Blanc behind us |

|

| The view from race central in Chamonix |

In the final 36 hours before the race, we took care of some logistical details, such as picking up my race bib and getting my equipment inspected. The race had an impressively long mandatory gear list for equipment you had to carry with you throughout the duration of the race, which thus required running with a pack that was tagged and spot checked throughout the race—shell jacket, shell pants, insulating layers for top and bottom, two headlamps, spare batteries, cell phone, survival blanket, spare food, minimum 1 liter water capacity, hat, gloves, and the list went on.

The day before the big event, we took the cable car up to the summit of the Aguille du Midi above 12,000 feet. The view of the heavily glaciated Mont Blanc massif from that rocky spire was simply stunning … and sobering. The race—starting on the other side of Mont Blanc in Italy and finishing here in France, with a route via Switzerland—was going to be a doozy.

We spent only about an hour atop the Aguille. I was wary of being on my legs for too long, so we retreated to the Plan du Midi cablecar station halfway back down to the valley, where we had a picnic lunch on the rocks. Then returned all the way to the Chamonix valley and headed back to our chalet, so I could make final preparations for the race and mostly stay off my feet to keep my legs fresher. They were gonna need every ounce of energy they could muster.

|

| Required gear laid out and ready to pack for the race |

Race morning began very early, with a short trip from Les Houches to Chamonix, where we caught the race buses that shuttled runners and spectators through the Mont Blanc Tunnel to the starting line in Courmayeur, Italy. It was hard to believe the moment had finally arrived!

The race began on the small central square of that tiny alpine village and there were no shortage of racers… about 1,900 of us in all. We had all qualified for the race and then been lucky enough to make it through the lottery. It seemed like at least 20 countries were represented. I saw bibs from pretty much every western European nation and Scandinavia, plus a number of countries from east Asia and the Americas.

I was bib number 5499, which put me in the first wave of three that would set off around 9:00am local time on a Friday. I also later learned that my bib number meant I was seeded number 499 out of the 1,900. We’d see how that prediction would play out!

As the appointed hour arrived, I kissed Kelli and then she took a position along the edge of the square from which she could watch the start, while I packed in shoulder to shoulder with the other runners behind the starting line. Some local schoolchildren dressed in traditional Aostan clothing performed a dance. Then we went through the three national anthems—Italian, Swiss, French—of the three countries through which we’d run. In the final moments before the starting gun, race organizers played loud, dramatic orchestral music that made us feel like we were about to do something important. It was like being in a real life movie trailer, and I’ll admit that it did get the adrenaline pumping just a little bit.

And then we were off. I was probably about a dozen or so people back from the front. The elite front runners took off like they were shot out of a cannon, sprinting out of the square. The pace seemed ridiculously and unsustainably fast. I thought, there’s no way they can sustain that. Apparently, a handful of them did. Much respect.

I set out to run conservatively. This was going to be a long day (and night). What’s the rush? I needed to meter out my energy reserves.

We wound our way through the narrow streets of Courmayeur, locals lining the streets and cheering us on as we left town. It was my first glance into the big deal that is European ultrarunning. They take the sport seriously and marquee events like this really bring people out, even on sections of the course where you’d expect it to be just you and the mountains. It’s kind of like the Tour de France, but for ultrarunners, and it was a stark contrast to the comparatively mellow scene of American ultrarunning.

Soon enough we left town and began a long, steady climb into the forest. That climb would go on, and on, and on. The race opened with a 4,000+ vertical foot climb to the 8,000+ foot summit of a mountain called Tete de la Tronche, the high point of the course.

This early in the race, before the field had a chance to spread out, we were basically one long human line of ants. As far as I could see up and down the mountain, the trail was one racer after another. We plodded upward.

Eventually, we broke out of the trees as we crested treeline into the alpine meadows and tundra above. That first view leaving the forest is one I hope I never forget. I popped out of the woods and looked up, and there before me was the entire south face of Mont Blanc—11,000 vertical feet of continuous relief, from the streets of Courmayeur (its rooftops visible far below) to the 15,000+ foot summit of Mont Blanc. Stunning.

Then it was back to the grind of the long, arduous climb.

As we neared the summit of Tete de la Tronche, a helicopter with a video cameraman hanging out its open door hovered just overhead. The race was broadcast live in Europe and streamed on the Internet as well.

Although the morning had started brisk, by now I was plenty toasty. Sweat dripped, almost continuously, off the brim of my cap. I thought I was doing the perfect job of rationing out my fluids—I was carrying two 20-ounce National Foundation for Celiac Awareness bottles. I finished the last of those fluids just five minutes before reaching the summit, the first checkpoint of the race. Perfect, I thought.

But as I crested the summit (2 hours 12 minutes elapsed) and race volunteers scanned my bib, I looked around and saw no water to be found with which to refill. That was at the next checkpoint, another 4.3 km downhill. Maybe there was a “lost in translation” language barrier. Or maybe it was the fact that this was the first ultra I’d run in which checkpoints and aid stations were not synonymous. But I was only now realizing that not every race control point offered fluids and food. Woops.

The 2,000 foot descent to the first aid station at Refuge Bertone really did a number on my quads. After that massive climb, and now this steep descent, I could feel that my quads were going to need careful monitoring throughout the course of the race. I didn’t want to blow them out too early, and I was worried that was already happening.

As I ran down the ridgeline, the view of Mt. Blanc was spread out before me. It was hard to strike a balance between appreciating the scenery and watching the trail ahead of me, so that I didn’t trip and take a dive.

After a relatively quick 35 minutes, I reached the aid station. I must’ve sucked down four or more cups of soda, I was so thirsty. Having taken the edge off my thirst, I could then focus on refilling both my bottles.

Other than fluids at aid stations, I had to be largely self-sufficient with my gluten-free nutrition during this race. I wasn’t going to reconnect with Kelli until the major aid station at Champex Lac in Switzerland, 56 km into the race, or about halfway. Until then I was on my own.

Aid station food at ultras is seldom very GF-friendly, and this race was no different, but with a European flair—pastries, croissants, baguettes. I was planning to supplement the calories I was carrying with fresh fruit from the aid stations, but even that was absent for the first quarter of the race or so.

No matter. I stuck to my own stash, planning to eat 250–300 solid calories per hour. Early in the race I planned to eat chocolate (mostly mini peanut butter cups and bite-size Snickers), then transition to Honey Stinger energy chews, and later into the race—when my stomach and thirst would inevitably make many foods less palatable—First Endurance EFS Liquid Shot. (Even deeper into the race, we cut the First Endurance 2/3 liquid shot with 1/3 water to thin it out. Amazing! Highly recommended. Goes down so easy.)

I stuck to this plan with OCD-like rigidity. I took a swig from my bottles every 10 minutes, having electrolytes from one bottle at :10, :30, and :50 after the hour and plain water at :00, :20, and :40 after the hour. Every hour on the hour I stopped to eat and keep the calories going in. Even if I thought I was only 15 minutes out from reaching the next aid station, I stopped. I’d later credit this unwavering commitment to my nutrition plan (and my training) for pulling me through the toughest race I’ve ever done.

After Refuge Bergone we turned up the next valley toward Refuge Bonatti. We were now running east, with the highest peaks of the Alps just to our north, including majestic Grand Jorasses. I soaked up the continually evolving panorama. I had considered carrying a small point-and-shoot camera for this race, and it’s a good thing I didn’t. Kelli knew why: “The race would have taken you hours longer! I can just imagine how many pictures you would have taken!” She’s absolutely right.

Soon I reached the next check point at Bonatti. I was already picking up some subtle nuances of the spectators that frequently lined the course. If they were from Italy, they tended to cheer “Bravo!” And if they were from Switzerland or France, then they cheered “Allez! Allez!” which is the equivalent of saying “Go! Go!” Our race bibs also had a tiny image of our national flag—seeing the red, white, and blue they’d sometimes also cheer “U. S. A!” Being a runner from overseas made me something of a novelty (in all there were 14 American finishers). And, through delightful French accents, I’d also be buoyed by cheers of “Go Pee-TEHR!”

After Bonatti, the next aid station was at Arnuva on the valley floor, followed by another stiff climb to the second-highest point on the course, the Grand Col Ferret. That high mountain pass marked our crossing from Italy into Switzerland.

By the time I reached it I was already more than 6 hours into the race and less than a third of the way to the finish. This was going to be a long grind. Before the race began, Kelli and I talked about how I planned to finish come hell or high water. Barring a truly catastrophic event, like losing a leg, I was not going to DNF this race. But it was becoming clear just how much a battle it was going to be.

As I crossed from one country into the next, the Grand Col was windy and cool, with some dark clouds swirling. I was grateful to begin descending into the next valley in the event that the weather opened up (it didn’t).

A magazine and ultrarunning colleague of mine back in Colorado who’s familiar with this part of the course had advised me ahead of time, “The descent into Switzerland is long and pounding. But you’ll be greeted by cows wearing real cowbells.” Wouldn’t you know it, he was right! As it descended, the trail clung to the mountainside above the valley floor. And from time to time I’d hear the tinkling of what sounded like cowbells. Sure enough, when I carefully scanned the lush, green meadows of the valley below, I’d spot a herd of Swiss cows, happily munching their way through this alpine Eden.

On the descent we passed another high-mountain hut, this one with several happy-looking old guys in sweaters drinking dark beers on the porch of the hut, watching us run by. A little farther on, I topped off my bottles from a mountain spring—throughout the Alps, such springs were often channeled into a steel pipe that poured into a small cistern. Very convenient!

At long last (7:45 elapsed) I reached the small Swiss village of La Fouly, the first real civilization I’d seen since leaving Courmayeur. I was now just 14 km from Champex Lac where Kelli would be waiting.

As I left La Fouly, the streets—as usual—were lined with spectators. One couple sitting on the side of the road, seeing Old Glory on my race bib, called out in perfect English, “An American! Where are you from?!”

“Colorado!” I hollered back.

“We’re from Colorado! Boulder!”

“Longmont!”

Unbelievable. Here we are thousands and thousands of miles away from home, and I come across folks who live just 12 miles from us back in Colorado. They sprang from their seats, I made a short diversion toward them, and we high fived before I continued out of town and back into the mountains. It was just the motivational boost I needed.

Then it was back onto the trails, paralleling a rushing mountain stream, then clinging to a cliffside, and then crossing into and through tiny Swiss villages. They were little enclaves, maybe a dozen houses or so each, with roads so narrow that as you ran between them you could outstretch your arms and nearly touch houses on both sides at the same time. The friendly residents stood in front of their houses and in their driveways to watch us go by. One house had even set up an impromptu aid station, with cups of water for us.

I was running now with a guy from France. We were deep enough into the race that the field had spread out, and I’m normally the kind of guy who likes to focus on running through the mountains in silence, but I appreciated the company. He spoke zero English, and very little Spanish (my main second language), so I butchered as much French as I could. That served us fine.

Eventually, though, I let him go ahead. It was time for me to stop briefly and eat again, during the climb up to Champex Lac, which was perched above in a hanging side valley. I never saw that runner again.

This video isn’t mine. It’s from French ultrarunner Bruno Poulenard, who placed just inside the top 100 in the race. He shot footage on his GoPro camera throughout the race. I make a few cameos (look for my white baseball cap and neon yellow shirt), but more importantly, in between shots of him, his video does an awesome job conveying some of the incredible mountain terrain through which we ran.

I arrived a Champex Lac at basically 10 hours on the nose. It was later than I’d hoped to arrive, but what are you gonna do? Looking at the course stats, and last year’s finish times, I thought that if I had a great race I could finish in around 15 hours. That clearly wasn’t happening; not by a long shot. (Upon closer inspection of the course later, I’d realize that this year race organizers added a major climb to the race (Tete de la Tronche) that added about 30% to finish times compared to last year.)

I was grateful to get to Champex Lac and reunite with Kelli. It’s pretty much a guarantee in longer races such as this that I’ll predictably hit a low point somewhere between miles 30 and 35. After that, I find a second wind and tend to have a strong back half of the race. Coincidentally, Champex Lac was at km 56 (~35 miles), so Kelli and I met up right when I was at rock bottom. In fact, I was feeling about as bad as I’d ever felt at this point in an ultra.

Sitting at a table inside the aid station tent, I wasn’t particularly conversational. Then I blurted out this line (as best as I remember it): “I didn’t plan on this when I started the race, but I’ve decided that the CCC is my semi-retirement from ultrarunning. I’m going to take all of 2014 off, spend more time with our family, and decide if I miss it enough to come back to ultrarunning later.” Kelli’s look of concern briefly changed into one of relief, as if she was thinking “You’ve finally come to your senses with this ultrarunning stuff!”

(Of course, by the time I saw her later at the Trient aid station, I’d pulled through the low point and was feeling much better. “That thing I said back there about retiring? I take it back,” I told her.)

|

| Arriving in Champex Lac, 54 km |

|

| Wait. I do this for fun? |

Since I only have a sample size of one, I don’t know how reflective the CCC is of other European races, but the aid station tent at Champex Lac was insane. Hundreds of people—racers and their crew—at row after row of picnic tables inside what felt like a giant white wedding tent. Racers were eating plates of pasta, bowls of soup, all manner of foods. Most of it was off limits for me, but that didn’t matter. My stomach wasn’t feeling especially cooperative. The best I could do was wedges of oranges and a few segments of sliced banana.

It was amazing how quickly time slipped by in that tent. I looked at my watch and realized that I’d been there for half an hour already! I could have watched an entire television program (with commercials)! It was time to get moving again before total inertia set in.

There were still three major climbs to go—over Bovine, Catogne, and Tete aux Vents—crossing into France along the way before a long descent to the finish line in Chamonix.

|

| Trient |

After sitting at Champex Lac for so long, it took a solid km or two to shake the cobwebs out of my legs, which had tightened up a bit and were feeling a little painful. It was now dusk, and the forest was growing darker as I began the climb up to Bovine. The stars began to come out and the temperature dropped quickly. Soon it was brisk and each exhalation was a big puff of foggy breath.

Before it got utterly dark I pulled out my headlamp but kept it turned off for the time being, choosing to let my eyes adjust to night as best as possible and preserving my battery life for the long overnight hours when I’d really need it. Later, I’d use my energy-efficient LED mode when moving more slowly on the uphills, and switched into a bright spotlight mode to better illuminate the trail when I was running faster on the downhills.

Just before breaking out of treeline onto the upper slopes of Bovine, I stepped off the trail and pulled a quick switch—stripping off my shorts and t-shirt and replacing them with long running tights and a long-sleeve shirt. It was getting downright cold out, and I only expected that to get worse, especially if there was any wind up above.

True to its name, there were plenty of cows at Bovine, hanging out in a meadow high on the mountain. One of them was “jogging” along the trail in front of me, so I fell in behind him as if he were a pacer. But when he suddenly realized I was behind him he didn’t seem to take that too kindly. He stopped abruptly, turned to face me, and took an aggressive posture (at least that’s what it seemed like at the time). I gave him a wide berth before moving on.

During the descent to Trient, I had what may have been my first-even ultra hallucination. I’ve heard about it happening to runners, and now maybe it’s happened to me. I was by myself, and looking ahead down the mountain, I was sure I saw the lights from the Trient aid station, heard a faint tingling of bells, and I would have placed a good bet that I heard the sound of spectators cheering. But when I got there, the “bright lights” of the aid station were a single, tiny light on the exterior of a darkened farm house. The bells proved to be yet another herd of cattle on the edge of forest and meadow. And the spectators? They were nowhere to be found. I was still a little ways out from the aid station, it turned out.

|

| Leaving Trient |

Hallucinations aside, I was bouncing back from my low point at Champex Lac. I was into a slow-and-steady groove, power hiking the uphills and running the flats and downhills. My quads were feeling it, to be sure, but the pain and fatigue had reached a sort of manageable steady state.

Next up was the climb over Catogne. At this point I was with a small pack of other runners. We were like the slowest, saddest, most silent conga line you’ve ever seen. One after the next, each head down, plodding uphill without a word.

From the top of Catogne, the course descended as much elevation as it’d gained from Trient, arriving next in Vallorcine. I was in a groove now. At Catogne I was in 571st place, but moving well on the descent, I started to pass runner after runner.

My silent mantra was “Do not fall! Do not trip! Stay on your feet at all costs!” repeated ad nauseum. At this point I’d been running for more than 16 hours and my legs—while still seeing me through—were pretty well shot. If I tripped on a rock or root, I didn’t have the energy to catch myself and get my legs back under me. I was going down, and I was going down hard. Better to avoid that outcome altogether.

I finally reached the aid station at Vallorcine around 2:00am, after just more than 17 hours. Kelli, as ever, was there waiting. She’s a saint!

|

| Leaving Vallorcine |

Vallorcine was my fastest aid station stop; at least ten minutes faster than Champex Lac or Trient. Things were good. I was making good conversation. (Hopefully she’d say the same thing!)

There was one major climb left—up and over Tete aux Vents. The climb came in two stages: 1) a mellow climb from Vallorcine up to Col des Montets, then 2) a very steep climb from the Col up and over Tete aux Vents. As I approached Montets, I could see the mountain in silhouette against the night sky, plus a line of headlamps from runners weaving their way up the mountain’s face. My first thought was, “Are they climbing a cliff?” It seemed impossibly steep.

Soon enough I was tackling the climb, switchbacking endlessly up the mountain. Every time I thought I’d crested the top, the mountain would rear up yet again. It was demoralizing. And cold. Earlier in the race it was so warm I literally had sweat pouring off the brim of my cap. Now there was a coating of ice on the rocks.

Eventually, I did reach the top of Tete aux Vents and begin the descent to Chamonix, passing through La Flegere, the last checkpoint. I paused only long enough to partially fill my bottles with water. From there it was more or less a steeply descending 10k to the finish line.

I had to stop once in the forest to replace my headlamp’s batteries, which frustrated me. The first light of morning was starting to show on the horizon, but not fast enough to illuminate the dark forest floor, and my headlamp was dimming. With a fresh set of batteries, I was good to go. In those last kilometers, I was really moving, passing tons of runners. Between Catogne and the finish line I’d pass nearly 70 people.

And then, suddenly, I found myself on the cobblestoned streets of Chamonix, running the final kilometer to the finish line arch in the center of town. Thousands of miles away and across the Atlantic, my aunt in New York was watching me finish live on the Internet stream. But where was Kelli?

I wasn’t across the finish line for more than ten minutes when she came running up, instantly bursting into tears. “What are you doing here?” she asked, getting her sobs and surprise and disappointment under control.

When we’d last seen each other, back at Vallorcine, we estimated how long it’d take me to reach the finish based on how I’d been moving. We ballparked 6 hours. She planned to get to the finish line in 4 hours, allowing a generous 2-hour buffer so she wouldn’t miss me. I beat the buffer by 7 minutes. Score one for finishing strong.

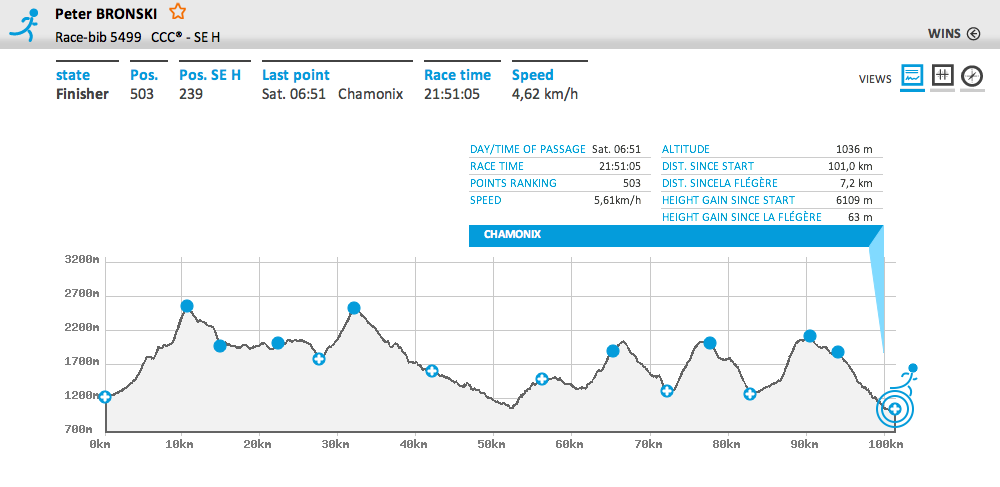

I finished in 21 hours 51 minutes, good for 503rd out of 1,900 starters and just over 1,300 finishers. (My uncle would later declare, “22 hours!? Even the things I love to do I don’t want to do for 22 hours.”) Final stats: 101 kilometers (62.75 miles) and 18,300 meters elevation change (41,000 vertical feet).

The CCC was farther than I’ve ever run by 10 miles, 19,000 more vertical feet than I’ve logged in a single run (nearly double), and longer than I’ve ever run by more than 9 hours (the first time I’ve started one day and run straight through the night and into the next morning).

Kelli and I snapped some photos together at the finish line and then headed back to the car to go back to our chalet and sleep for a few hours. We’d come back to town later that morning to enjoy the race festivities and the finish of the UTMB, another major race taking place. It’d been a long night for both of us.

Back at the chalet, our wonderful hosts had set out some bath salts for me to soak my tired legs. Kelli drew the bath for me then went to bed. I sat in the tub, and four different times, I was so tired that I fell asleep sitting there, only waking up when I tipped forward and my face hit the water. After the fourth time, I decided enough was enough. Sit bath or not, it was time to go to bed. CCC? Mission accomplished. Check that box on the bucket list.

|

| Proudly sporting my finisher’s vest the next day |

–Pete

Wow! That was quite an accomplishment Pete! Your telling of the story had me glued to the computer screen to the end.